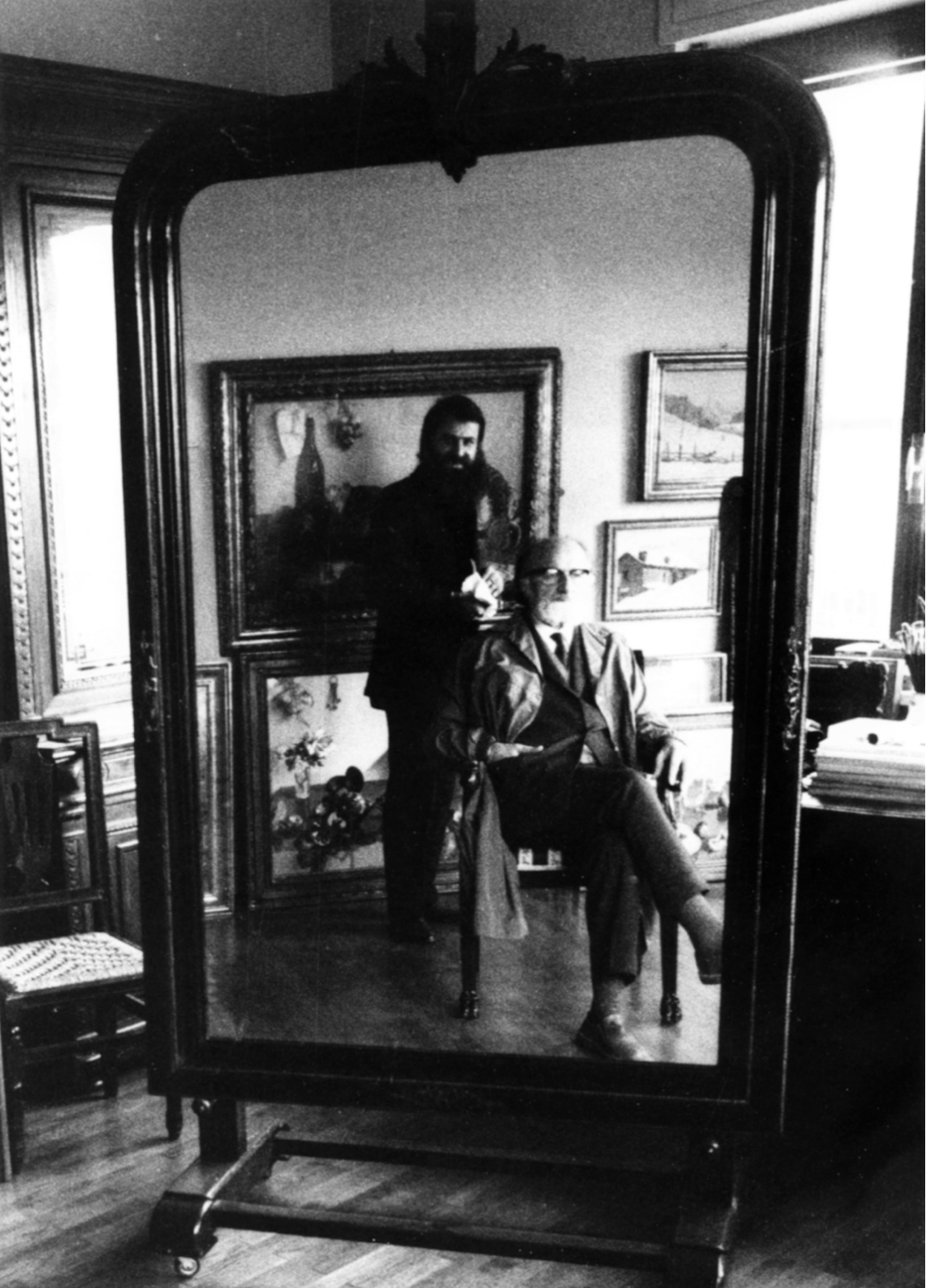

Michelangelo Pistoletto at Cittadellarte, Biella, (photo Uscha Pohl)

Born in 1933, the star of Michelangelo Pistoletto has brightened the sky of the international art world for 70 years. Having gained widespread recognition early on through his ‘mirror paintings’ and as one of the leaders of the ‘Arte Povera’ movement, in the 90s he turned his utopia into reality with the Fondazione Pistoletto-Cittadellarte in Northern Italy. Known as both artist and theorist, he acts as a catalyst for knowledge and advancement of social behaviour, promotes understanding and calls us to personal responsibility.

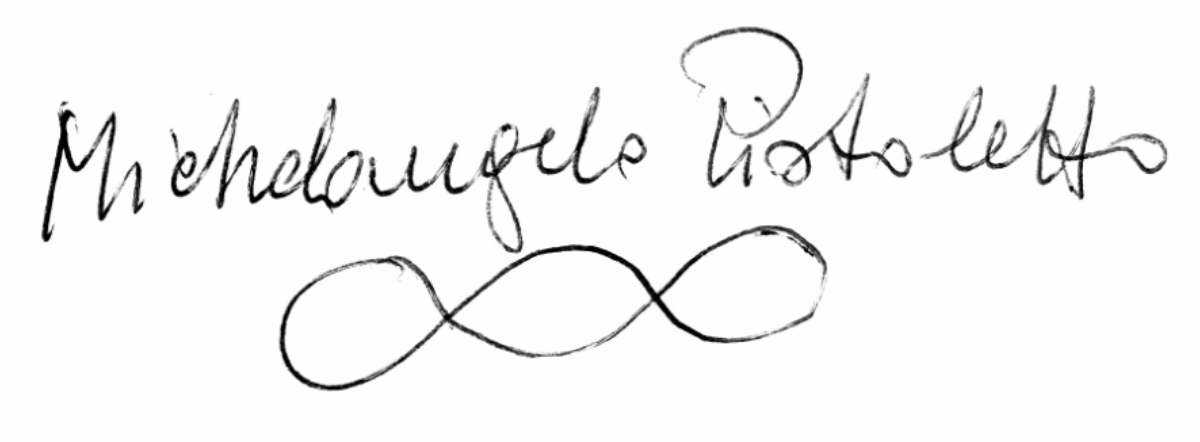

Unlike Atlas, man cannot carry the earth as one. Michelangelo Pistoletto seeks creative collaboration and the expansion of circles — represented by an extension of the horizontal figure ‘8’ (‘infinity’).

The iconic triple-loop symbol of Terzo Paradiso / “Third Paradise” stands for humanity’s new phase in which humans reunite with nature from which they became separated. Originally, humans like animals lived in harmony with nature. That was the First Paradise. Then, since the discovery of the “I” — symbolized by the first handprint on prehistoric cave walls — humanity developed progressively egocentrical. We dissociated from nature to the point where we are knowingly, actively and vehemently destroying Mother Earth, our source. This is the Second Paradise, where humans, their increasingly artifical world and nature drift ever further apart.

Today, Michelangelo Pistoletto says, we have reached the understanding necessary to enter the next phase: the Third Paradise, where we reconcile with nature and nurture it with honour instead of destroying it — and ourselves — in an act of grotesque self-annihilation. He calls on us to step up and through unity and collaboration, engage in the joint cause of nature and humanity. Knowledge and freedom purport responsibility.

Extracts from a Conversation with Michelangelo Pistoletto, Cittadellarte, Biella

My father was an artist — growing up I was surroun- ded by the smell of paint and paintings. My mother cooked, and my father painted what we ate. Art was my nourishment, and my nourishment became art,” laughs Michelangelo Pistoletto. “Art was handed to me in the cradle.”

“The concept of ‘family’ is very important to me. My parents were wonderful people, honest with their enti- re lives. They were already in their thirties when I was born as their only child. My father, Ettore Pistoletto Olivero, began painting early, sketching the frescoes of the church across the street from school when drif- ting off a lesson. He had lost his hearing at the age of eight due to illness — he could converse and lip-read one-on-one, but group situations were difficult. We had no radio so as not to exclude him, no music at home. As a result, the other senses were sharpened— especially the eye.”

Michelangelo Pistoletto’s home region Biella / Pied- mont (“foot of the mountain”) historically benefitted from its geographic location — mountain sheep sup- plying fine wool, water power fuelling textile mills, and the fertile and humid Po Valley enabling thriving agriculture. Proximity to France, Milan and the coast ensured robust trade and cultural exchange. The city of Turin has a rich intellectual and political history, was the first capital of the kingdom of Italy (1861-65) and played a central role in the resistance during WWII. The menswear empire Zegna has its headquar- ters in Trivero in the mountains above Biella; founder Ermenegildo Zegna commissioned Ettore Pistoletto Olivero for extensive series of frescoes and paintings for his company, and his son Aldo Zegna would beco- me Michelngelo Pistoletto’s first collector.

“At the age of forteen I began working in my father’s art restoration studio where my father taught me a great number of techniques. He didn’t believe in art academy education, which ‘would only corrupt me’. My mother on the other hand saw a future in advertising and enrolled me in the Armando Testa advertising design school. Now, Testa had made six months study of modern art an entry requirement for the school. It was through this detour that I discovered modern art and its freedom—and later never took up the offered job at the agency.”

“The crisis of representational art, triggered by the invention of photography in the 19th century, had raised many questions which some sought to answer collectively in groups, others individually. For me, it meant introspection: rather than depicting visible reality, I wanted to make the inner world visible, answer the question, ‘Who am I?’”

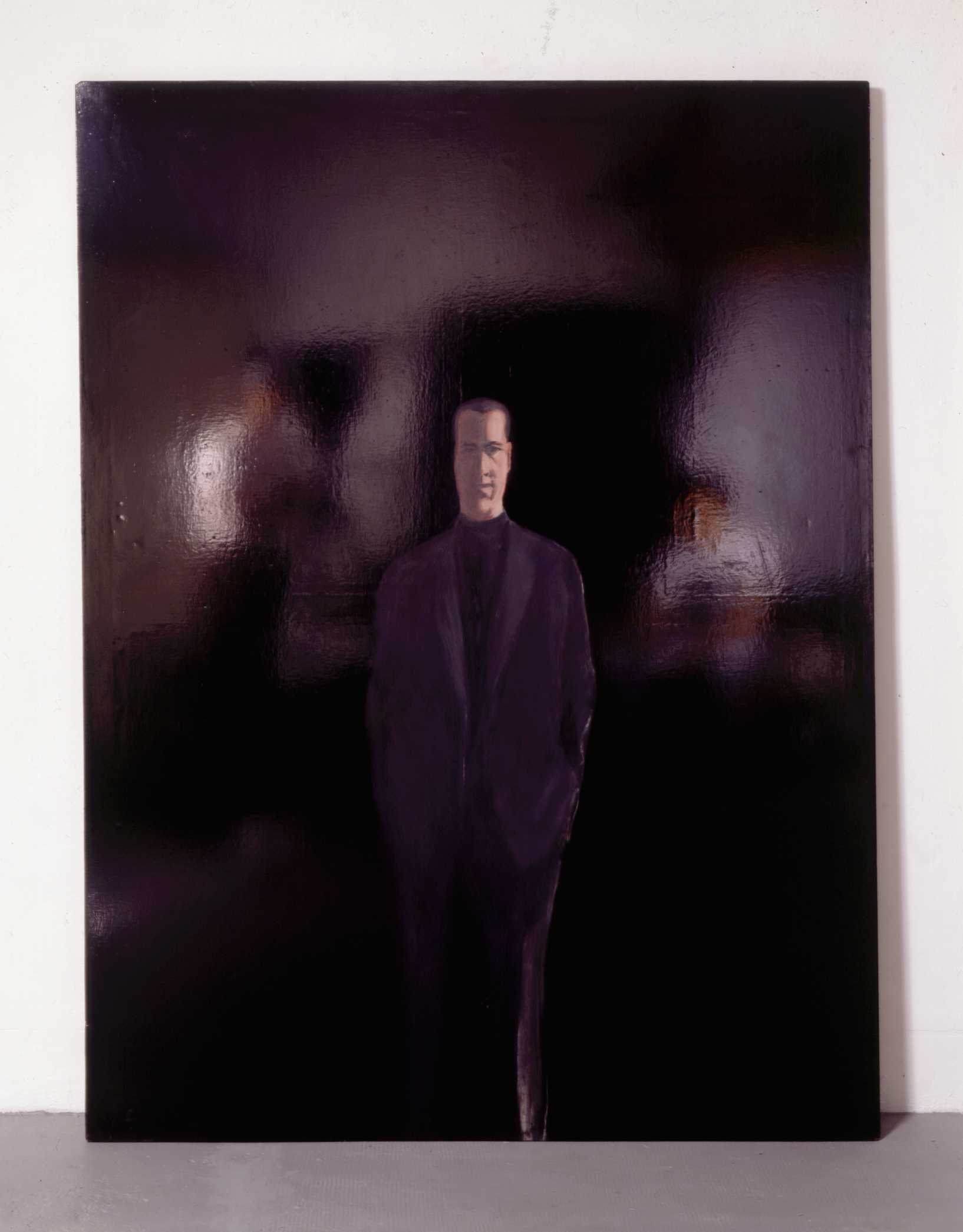

Exhibiting since 1955, in 1961, a self-portrait on a deep black glossy background had a profound impact. “The surface was so dark and shiny that it resembled a mirror. The image rendered the reflection of the surrounding space and events just as much as the painted elements, creating a new dimension. A picture emerged that I hadn’t painted — dynamic, interactive, timeless, containing both visible and the unforeseeable elements: it represented the past, present, and future in one.”

“The past is the painted image which has become a memory; the present is the moment of viewing reflected in the mirror; the future is implied in the potentiality of what is yet to be reflected. The ‘Mirror Painting’ is an expression of space-time-infinity and thus the phenomenology of our existence. I realized then that scientific aspects were integral to my research.”

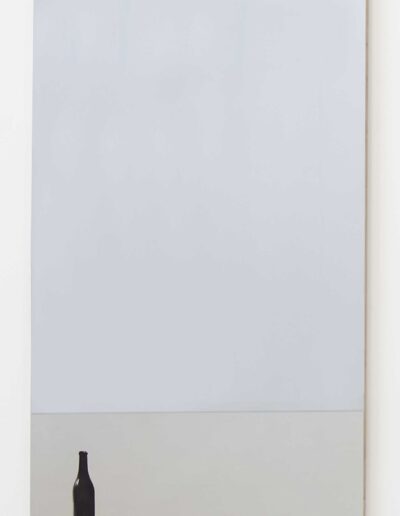

“Gold, the most durable material on Earth, symbolizes transcendence in iconology. Polished stainless steel, which equally doesn’t oxidize, became the base of the ‘Mirror Paintings,’ where screen prints or painted images (memories) are combined with the infinite potential of the mirror surface. The ‘Metrocubo’— a closed cube that reflects itself ad infinitum — is a direct representation of infinity. But infinity requires the finite, a reference point. The physical object signifies time and duration; the depiction represents the moment, the immediate.”

“As humans, we have the ability to reflect on ourselves and the universe. Since ancient times, man has pondered the invisible, intangible. It is human to want to know what lies beyond the horizon, the stars, the galaxy. What animals accept, humans question in search of insight.”

“Since the first handprint in a cave, we have recognized the virtual as an enduring medium — more than mere representation, art and human creations became our identification. The virtual unleashes immense possibilities, and artificial intelligence continues to open new dimensions. With AI, just like with all other inventions, we must be aware of our responsibility.”

Politics and art are inextricably linked in the case of Michelangelo Pistoletto, yet events in 1964 had particularly far-reaching consequences.

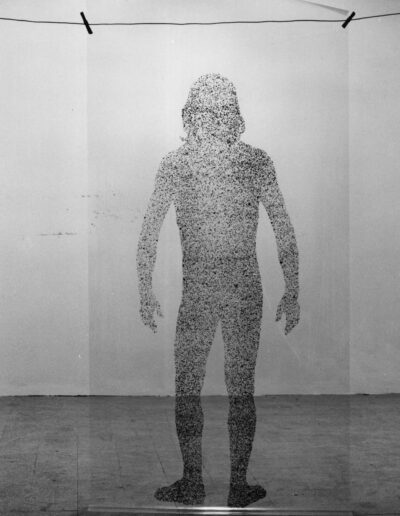

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Autoritratto di stelle, 1973, fotografia su pellicola trasparente, cm 200 x 105, Foto: Paolo Pellion

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Il presente – Uomo di fronte, 1961, acrilico e vernice plastica su tela, cm 200 x 150, Foto: Paolo Pellion

”Drawing Bottiglia,” 1963, fotografia su acciaio inox lucidato a specchio cm 180 x 120, Foto: Archivio Pistoletto

Gallerist Ileana Sonnabend (née Schapira, Bucharest) and her first husband Leo Castelli (né Krausz, Triest) managed to flee Paris in the 1940s through her extensive international contacts. Having worked with European artists and surrealism in Paris, in New York they went on to promote American art. In 1959, just divorced and newly married to Michael Sonnabend, Ileana Sonnabend opened her ‘Sonnabend gallery’ back in Paris. She remained not only good friends with her ex-husband Castelli but actively collaborated with his gallery. Both central figures of the transatlantic art scene, in the early 1960s the duo represented Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol among others.

In spring 1963, Sonnabend bought Pistoletto’s entire Mirror Paintings exhibition from Galeria Galatea in Turin and signed him to her gallery. That December, she included Pistoletto in the group exhibition Dessin Pop, followed by his solo debut in March 1964. Now represented by Sonnabend in Paris and Castelli in New York, Pistoletto found himself projected onto the international stage. It was a turbulent year: “In 1964, Robert Rauschenberg had won the Venice Biennale Grand Prize for Painting. Nothing like that had ever happened. It was a huge triumph for America.1”

With the U.S. deeply invested in the Cold War as well as a ‘Cultural Cold War’, the Biennale win was a massive propaganda success. The cultural offensive intensified, the wheels started to turn at new levels.

“At the time Sonnabend/Castelli publicized the art of the galleries summarily as ‘Pop Art’— ‘Popular Art’ — which promoted the American lifestyle, glamorized ‘low culture’ and made art accessable to wider audiences. Now I was the only Italian, the only European, the only non-American among the artists. I was a problem. At the end of 1964 I arrived in New York, having worked hard for a solo exhibition with all previous work sold and/or placed in museums. I was in a taxi, sandwiched between Leo Castelli and Alan R Solomon (who had curated the American pavilion at the 1964 Venice Biennale with Rauschenberg)2, — when Castelli gave me an ultimatum:

‘We’ll give you ‘everything — ‘, under one condition: you must come to America, become American, forget you were ever European, and change your name. You need to be part of ‘the family’. If you don’t, you’ll be nothing, and nothing will become of you —.’”

“I chose ‘nothing.’ I didn’t want to become a tool of propaganda for American consumerism, surrender my artistic freedom and become a cog in the system. ‘Pop Art’ had turned from ‘popular’, to ‘populist’,‘absolutist.’”

“I returned to Turin, and the following works — the Minus Objects — were all fundamentally different from one another as to avoid any recognizable artistic signature. With this ‘No Label’ stance, I aimed to destroy marketability, destroy myself as an artist, become ‘nothing’ — by choice. The name Minus Objects means ‘infinite possibilities, minus the one you have just realized.’”

Rather than glorify consumption, Arte Povera3 sought the essential. “Arte Povera is not ‘poor art’ but ‘radical art’ — radical as in ‘root’, ‘origin’—‘radice’ in Italian, ‘radix’ in Latin.” The actions and performances of the loosely formed artist group Zoo then continued this theme through collaborative works outside of the ‘system.’

“It was liberating to take to the streets, to act outside traditional structures, to be independent. Autonomy is important to me. I sought objectivity; mirrors reflect everything without exclusion and thus are by definition objective. Conscious action — and the freedom to carry it out — means responsibility. Responsibility brings us to spirituality — whatever name we give it. Through the spirit emptiness becomes fullness; the unfilled space between all things becomes ‘something.’ Quantum science shows that something — and therefore everything — behaves differently when it has a witness. Consciousness changes reality. The moment we think we understand something, it changes and escapes us. 1 plus 1 equals 3… In nature, when two merge, a third new entity is born — so we are constantly evolving… I contribute what I can.”

1) The documentary film “Taking Venice” (2023) by Amei Wallach investigates the scandal surrounding the US government’s manipulation of the award ceremony in Venice in 1964. (2) In 1963, Alan R Solomon, then director of the Jewish Museum in New York, had organized major solo exhibitions for Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. (3) The term “Arte Povera” (“poor art”) was coined in 1967 by art historian and curator Germano Celant, who highlighted the humanistic and social approach as well as the preference for used materials of artists such as Michelangelo Pistoletto, Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, and Alighiero Boetti.

Metrocubo d’infinito (Oggetti in meno 1965-1966), 1966, dettaglio dell’opera, Foto: Stefano Bergomas

Mappamondo (Oggetti in meno 1965-1966), 1966-2016, giornali pressati, ferro diametro cm 210, Foto Stefano Bergomas

The Third Paradise Perspective, 2025 Corderie dell’Arsenale, Venezia A cura di Cittadellarte, Tiziano Guardini, Luigi Ciuffreda, Giulia Giavatto In occasione della 19° Mostra Internazionale di Architettura Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective, Foto Riccardo Banfi

Terzo Paradiso:

“Our personal decisions have an effect on the entire world” Michelangelo Pistoletto

Michelangelo Pistoletto is a man of both theory and action. Art as decisive factor in humanity’s evolution is fostered through his multifacetted work, which includes:

In 1998, opening the Fondazione Pistoletto– Cittadellarte art complex in a spacious former wool factory in Biella was as a real-world implementation of Pistoletto’s 1994 Progetto Manifesto. 1999 saw the launch of the UNIDEE residency program for art and social transformation which celebrated its 25th anniversary in September 2024.

The Love Difference project launched in 2002 continues to raise awareness for the political hotspot of the Mediterranean. April this year, UNESCO inaugurated Pistoletto’s installation Love Difference at its Paris Headquarters.

2003 Pistoletto received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale, where he has exhibited thirteen times to date. Since its inception in 2003, the Terzo Paradiso project has hosted 2000 events, established close to 300 “Cultural Embassies” with 5 mio participants around the world. The project Spac3, brought Terzo Paradiso to the International Space Station as a photographic group project in collaboration with the European Space Agency.

In 2012, the concept of Demopraxy was born, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Paolo Naldini, replacing kratos (power) in the word democracy with praxis (practice).

2019 Unidee Academy opened, offering an international program of art and fashion with sustainability, innovation and social transformation at its core.

2023 the concept Statodellarte (State of Art) with its segments ‘Unity of Religions’, ‘United Enterprises’, ‘Unity of Sports for Preventive Peace’ are presented.

2024 Pistoletto received an honorary degree in Political Science from the University of Turin.

2025 Michelangelo Pistoletto is nominated for the Nobel Prize for Peace. His Terzo Paradiso Perspective installation, currently on display at the 19th Venice Architecture Biennale, lets us experience a notion of the advancing climate heating emergency and rising sea levels.

Cittadellarte is structured in seven different ‘uffizzi’ (offices): Art, education, politics, fashion, nutrition, architecture, spirituality. The extensive complex now stretches for kilometers along the Cervo river and in 2026 the new 4-star Hotel Cittadellarte is set to welcome the first guests. —Uscha Pohl

Ways of Becoming: 25 years of UNIDEE”; Juan Esteban Sandoval with Michelangelo Pistoletto; Charlie Hamish Jeffery

“Shouting” Video 7 min, 1998; Cees Krijnen, “Social Sustainability, Generations Together 1979- 2024”, Cees Krijnen, 2024; Mako Ishizuka workshop

Current exhibitions:

Mirror in Time, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Erinna König, UP&CO @ EK STUDIO

Michelangelo Pistoletto, ‘La Soglia (‘The Threshold’) Galleria Continua, via dell Castello 11, 53037 San Gimignano, Italy

galleriacontinua.com

Picasso/Pistoletto, Nahmad Projects, 2 Cork St. London W1S 3LB London

nahmadprojects.com